Free Resources

Downloadable .pdf version of the article: Negative Religious Coping, Negative Affectivity and Emotional Disorders

Abstract

Religion is a significant component for helping individuals navigate, conceptualize, and respond to life stressors and is not exclusive to one culture or religion. Several religious groups, cultures, and individuals have engaged in religion as a means to cope with various life situations and emotional disorders. Further, common to the human experience is the experience of affectivity, specifically negative affect. Negative affect is commonly experienced when facing problematic circumstances such as death, emotional disorders, and even religion itself. Negative affect has additionally been identified as neuroticism which is linked to the development and maintenance of emotional disorders. Given the commonality of experiencing negative affectivity and the utilization of religion as a means to cope with difficult circumstances, the present study aimed to investigate the relationship between negative religious coping (NRC) and negative affectivity (NA). Twenty participants were provided with two surveys assessing NA and NRC. Results revealed a strong positive correlation between NRC and NA. Further areas of investigation are discussed within the context of the present study’s findings. One such area includes the relationship between personality traits, religious scrupulosity obsessive-compulsive disorder (RS-OCD) and Christianity, specifically Pentecostal and Charismatic congregations.

Keywords: psychology, Christianity, science, religious scrupulosity, neuroticism

Negative Religious Coping, Negative Affectivity and Emotional Disorders

Religion in the United States is a practice used to help cope with life stressors and the accompanied experienced negative affectivity (Gall et al., 2013; Paika et al., 2017; Pargament et al., 2011). Indeed, an abundance of literature affirms the function religion plays in responding to stress and negative affectivity experienced through a variety of life circumstances (Koenig et al., 1992; Schusteret al., 2001; Meisenhelder & Marcum, 2004; Ano & Vasconcellos, 2005; Chapman & Steger, 2010; Pargament et al., 2011; Gall et al., 2013; Paika et al., 2017; Rosa-Alcázar et al., 2021). Similarly, with regard to individuals suffering from emotional disorders, religion has been identified as a significant coping strategy irrespective of culture or religious practice (Bhui et al. 2008; Chapman & Steger, 2010; Nurasikin et al., 2012; Feder et al., 2013; Tavernier et al., 2019). Neurobiological research has identified several correlates between the effects religious coping has on regions of the brain in relation to emotional disorders (Rosmarin et al., 2024). Brain regions include orbitofrontal cortex, posterior cingulate cortex, insula, frontal cortex, and default mode network (DMN; Rosmarin et al., 2024). Taken together, religion plays a significant part in coping with the unpredictable and uncontrollable life experiences and emotional disorders.

Provided the function of religion with regard to coping with life stressors, responding to negative affectivity, and experiencing emotional disorders, researchers and clinicians have utilized findings to develop and implement psychological and spiritual interventions for those experiencing life crises, navigating stressful situations, and better understanding the impact of affect variability (Gall et al., 2013; Tarakeshwar et al., 2005; Pargament et al., 2011). One psychometric inventory assessing religious coping was developed by Pargament et al. (2011) labeled the Brief RCOPE. The Brief RCOPE is a condensed psychometric inventory derived from the Religious Coping Activity Scale (RCOPE; Chapman & Steger, 2010; Pargament et al., 2011; VanderWeele et al., 2017) and is widely used to assess religious coping regarding ordinary life stressors, medical stress, and emotional disorders (De Berardis et al., 2020; McGrady et al., 2021; Paika et al., 2017; VanderWeele et al., 2017). Further, the Brief RCOPE is designed to assess a two-factor construct of religious coping, positive and negative. Positive religious coping is associated with a stable and secure relationship with God, an intrinsic axiom that life has an inherent generous meaning, and a sense of connectedness with a divine force (Pargament et al., 2011). Negative religious coping is associated with spiritual tension, negative affectivity, fractured connectedness with God, spiritual doubt, and religious discontentment (Chapman & Steger, 2010; Pargament et al., 2011).

It is self-evident, and empirically identified (Chapman & Steger, 2010; Pargament et al., 2011) that life is associated with experiences that manifest variability of affect. Though affectivity has dimensional affective structures, positive and negative, high negative affectivity is evident when experiencing life stressors, medical uncertainty, emotional disorders, and spiritual tension. Negative affect (NA) is a subjective experience that is characterized as distress, anger, contempt, fear, nervousness, and guilt (Watson & Clark, 1988). Though easily misunderstood, negative affect is best conceptualized on a continuum between high and low (Watson & Clark, 1988). High negative affect is associated with fear, anxiety, anger, and contempt, while low negative affect is characterized as calm and tranquil (Clark & Watson, 1988). Further, trait NA has shown to be related to the personality dimension neuroticism (Clark & Watson, 1988). Recent empirical studies have shown neuroticism to predict and is linked to several psychological disorders, presenting comorbidities among psychological disorders, and the increased use and cost of health services (Barlow et al., 2014; Sauer-Zavala & Barlow, 2021).

Provided empirical evidence of many seeking religion as a means to cope with life stressors, medical uncertainty, and emotional disorders (Koenig et al., 1992; Schusteret al., 2001; Meisenhelder & Marcum, 2004; Ano & Vasconcellos, 2005; Chapman & Steger, 2010; Pargament et al., 2011; Gall et al., 2013; Paika et al., 2017; Rosa-Alcázar et al., 2021), it is important to further understand the relationship between negative religious coping and negative affectivity. Indeed, as negative affect is associated with neuroticism, and neuroticism empirically identified as a significant psychology vulnerability in the development of psychological disorders, emotional dysregulation, and increased medical services (Barlow et al., 2014; Sauer-Zavala & Barlow, 2021), expanding the scientific knowledge regarding negative affect and negative religious coping is advantageous. Thus, the present study aims to better understand the relationship between negative religious coping and negative affectivity. The alternative hypothesis expects a positive correlation between negative affectivity and negative religious coping (NRC).

Method

Participants

Twenty participants completed the survey regarding NA and NRC. All participants were older than 18 years of age. Participants’ age ranges were from 25 – 85 with a mean of 41 and a standard deviation of 15.43. The survey was distributed to participants via Facebook Messenger and short message service (SMS) text messaging. All participants were either family or friends of the researcher. The message regardless of platform contained a hyperlink to the survey.

Materials

A survey assessing NRC and NA was developed utilizing Mailchimp survey creation tool. The survey has one demographic question which provided participants the opportunity to manually enter their age. Regarding NRC, the Brief RCOPE negative religious coping subscale (Pargament et al., 2011) was used. Internal consistency varied depending on the population. The lowest reported Cronbach alpha was 0.60 among Pakistani undergraduate students (Pargament et al., 2011). The highest reported Cronbach alpha was 0.90 among cancer patients (Pargament et al., 2011). The median identified Cronbach alpha was 0.81 (Pargament et al., 2011). NRC consists of a 4-point Likert scale and 10 questions.

Assessing NA, the subscale NA from the final version of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; Watson & Clark, 1988) was utilized. PANAS NA showed high internal consistency with a reported Cronbach’s alpha of 0.87 (Watson & Clark, 1988). Further PANAS NA demonstrated statistically high Cronbach alpha across every time period assessed, 0.86 (Year) to 0.90 (Today; Watson & Clark et al., 1988). The PANAS NA consists of seven questions assessed on a 5-point Likert scale.

Procedure

A link to a web form using the Mailchimp platform was distributed directly to participants via Facebook messenger in SMS text messages. The link consisted of a survey disclaimer and instructions. Data collected utilizing Mailchimp was loaded into SPSS version 29.0 (241) for statistical analysis.

Analysis

Measuring PANAS NA a five-point Likert-based question was used. Scores ranged from 1 (Verly slightly or not at all) – 5 (Extremely). Following scoring instructions from Watson and Clark (1988), total PANAS NA scores were calculated by summing all scores from the participant’s selection. Total score range is from 10 – 50. A score of 10 indicates low levels of negative affect, whereas a score of 50 indicates high levels of negative affect (Watson & Clark, 1988). Regarding NRC participants responded to 7 questions utilizing a four-point Likert scale. Scores ranged from 1 (Not at all) – 4 (A great deal). A total NRC was calculated following summing participants’ scores for each question. Total score range is from 7 – 28. Higher scores are interpreted as participants having more negative religious coping (Pargament et al., 2011). A Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient was computed to determine the relationship between NRC and PANAS NA. IBM SPSS statistics (Version 29.0, 241) were used to statistically evaluate the relationship. An alpha level of .05 was used to determine statistical significance.

Results

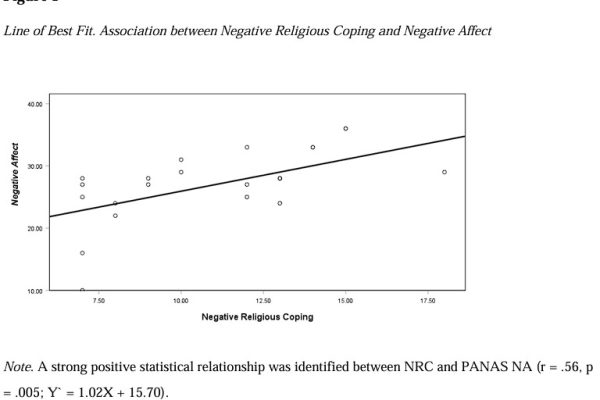

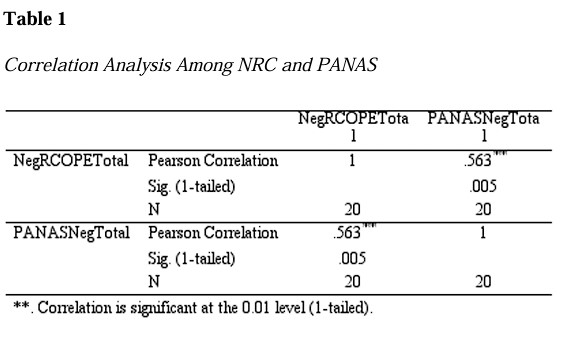

The present study investigated the relationship between negative religious coping (NRC; Pargament et al., 2011) and Negative Affect (NA; Watson & Clark, 1988). The alternative hypothesis asserted a positive correlation between NRC and NA. Pearson’s r correlation revealed a strong, statistically significant positive correlation between NRC and NA (r = .56, p = .005, 95% CI [.234, 1.00], one-tailed), supporting the alternative hypothesis (see Table 1). Line of best fit was computed, further supporting a strong positive correlation between NRC and NA (F (1, 18) = 8.4, p = .010, see Figure 1).

Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to examine the relationship between NRC (Pargament et al., 2011) and NA (Watson & Clark, 1988). Results from this study indicated a strong positive correlation between NRC and NA. These results are consistent with findings from Chapman and Steger (2010), investigating the relationship between religious coping and anxiety related symptoms. Further results from this study were congruent with neurobiological examination between the correlates of NRC, NA, emotional disorder, and brain regions implicated with experiencing negative affect (Rosmarin et al., 2024).

While the present results are consistent with existing empirical investigation, it is important to acknowledge, though Chapman and Steger (2010) examined symptoms of anxiety rather than trait negative affect (NA), literature observes symptoms of anxiety as integral to NA, more recently identified as neuroticism (Barlow, 2002; Barlow et al., 2014; Barlow & Kennedy, 2016; Sauer-Zavala & Barlow, 2021). Indeed, recent research has revealed a higher order dimension, neuroticism, as a transdiagnostic vulnerability in the expression and development of emotional disorders. Emotional disorders include anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder (Inozu et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2024), panic disorder, agoraphobia, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (Rosellini & Brown, 2011; Sauer-Zavala & Barlow, 2021). Though the present study did not directly examine the relationship between emotional disorders and NRC, the study did provide consistent findings with proximal empirical results between NA (anxiety symptoms) and NRC (Chapman & Steger, 2010). Furthermore, these findings support further investigation into the relationship between NRC, neuroticism, and emotional disorders as emotional disorders are highly correlated with increase medical expenses and life dissatisfaction (Barlow et al., 2014; Sauer-Zavala & Barlow, 2021). Provided the results of this study, focusing future research on a specific emotional disorder, namely, religious scrupulosity obsessive-compulsive disorder (RS-OCD) will be advantageous, as RS-OCD involves significant psychological distress relating to one’s religion and is an understudied presentation of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD; Abramowitz et al., 2002; Abramowitz & Jacoby, 2014). Further, given the results of the present study, religion being a vital function to cope with life stressors (Koenig et al., 1992; Schusteret al., 2001; Meisenhelder & Marcum, 2004; Ano & Vasconcellos, 2005; Chapman & Steger, 2010; Pargament et al., 2011; Gall et al., 2013; Paika et al., 2017; Rosa-Alcázar et al., 2021) , RS-OCD being an understudied presentation of OCD (Abramowitz et al., 2002; Abramowitz & Jacoby, 2014), and the increased medical services with regards to emotional disorders (Barlow et al., 2014; Sauer-Zavala & Barlow, 2021) practically partnering with religious communities to educate religious leadership of the link between NRC, NA, and emotional disorders would be advantageous.

Though results supported the alternative hypothesis, the present study is not without limitations. The sample was restrictive to friends and family of the researcher, some of whom may identify as atheist, agnostic, or hold no spiritual or religious convictions. Further, several other confounding variables could have influenced participant rating of NA at the time of assessment completion such as psychopathologies, current mood, and life stressors. Future studies may want to include questionnaires relating to diagnosed psychopathology, a survey regarding present life stressors, a questionnaire with regards to participants’ religious affiliation, religious commitment, and personality dimensions, such as neuroticism, extraversion, agreeableness and consciousness. In addition, future studies may consider narrowing the sample to specific church congregations or specific Christian denominations such as Pentecostal and Charismatic oriented Christians and church communities. In summary, as it is well documented that religion in the United States is a central practice utilized to navigate and cope with life stressors (Gall et al., 2013; Paika et al., 2017; Pargament et al., 2011) and emotional disorders (Chapman & Steger, 2010; Rosa-Alcázar et al., 2021) it would be advantageous to continue investigating facets of negative affectivity, RS-OCD, and Christianity.

References

Abramowitz, J. S., D. Huppert, J., Cohen, A. B., Tolin, D. F., & Cahill, S. P. (2002). Religious obsessions and compulsions in a non-clinical sample: The Penn Inventory of Scrupulosity (PIOS). Behaviour Research and Therapy, 40(7), 825-838. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(01)00070-5

Abramowitz, J. S., & Jacoby, R. J. (2014). Scrupulosity: A cognitive–behavioral analysis and implications for treatment. Journal of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders, 3(2), 140-149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocrd.2013.12.007

Ano, G. G., & Vasconcelles, E. B. (2005). Religious coping and psychological adjustment to stress: A meta-analysis. J Clin Psychol, 61(4), 461-480. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20049

Barlow, D. H. (2002). Anxiety and its disorders: The nature and treatment of anxiety and panic, 2nd ed. The Guilford Press.

Barlow, D. H., Ellard, K. K., Sauer-Zavala, S., Bullis, J. R., & Carl, J. R. (2014). The origins of neuroticism. Perspect Psychol Sci, 9(5), 481-496. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691614544528

Barlow, D. H., & Kennedy, K. A. (2016). New approaches to diagnosis and treatment in anxiety and related emotional disorders: A focus on temperament. Canadian Psychology, 57(1), 8-20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/cap0000039

Bhui, K., King, M., Dein, S., & O’Connor, W. (2008). Ethnicity and religious coping with mental distress. Journal of Mental Health, 17(2), 141-151. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638230701498408

Brown, T. A., Chorpita, B. F., & Barlow, D. H. (1998). Structural relationships among dimensions of the DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders and dimensions of negative affect, positive affect, and autonomic arousal. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 107(2), 179-192. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.107.2.179

Chapman, L. K., & Steger, M. F. (2010). Race and religion: Differential prediction of anxiety symptoms by religious coping in African American and European American young adults. Depression and anxiety, 27(3), 316–322. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20510

De Berardis, D., Olivieri, L., Rapini, G., Serroni, N., Fornaro, M., Valchera, A., Carano, A., Vellante, F., Bustini, M., Serafini, G., Pompili, M., Ventriglio, A., Perna, G., Fraticelli, S., Martinotti, G., & Di Giannantonio, M. (2020). Religious coping, hopelessness, and suicide ideation in subjects with first-episode major depression: An exploratory study in the real world clinical practice. Brain Sci, 10(12). https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci10120912

Feder, A., Ahmad, S., Lee, E. J., Morgan, J. E., Singh, R., Smith, B. W., Southwick, S. M., & Charney, D. S. (2013). Coping and PTSD symptoms in Pakistani earthquake survivors: Purpose in life, religious coping and social support. Journal of Affective Disorders, 147(1), 156-163. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2012.10.027

Gall, T. L., & Guirguis-Younger, M. (2013). Religious and spiritual coping: Current theory and research. In APA handbook of psychology, religion, and spirituality (Vol 1): Context, theory, and research. (pp. 349-364). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/14045-019

Inozu, M., Kahya, Y., & Yorulmaz, O. (2020). Neuroticism and Religiosity: The role of obsessive beliefs, thought-control strategies and guilt in scrupulosity and obsessive-compulsive symptoms among Muslim undergraduates. J Relig Health, 59(3), 1144-1160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-018-0603-5

Koenig, H. G., Cohen, H. J., Blazer, D. G., Pieper, C., Meador, K. G., Shelp, F., et al. (1992). Religious coping and depression among elderly, hospitalized medically ill men. American Journal of Psychiatry, 149, 1693–1700.

Meisenhelder, J. B., & Marcum, J. P. (2004). Responses of clergy to 9/11: Posttraumatic stress, coping, and religious outcomes. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 43, 547–554

McGrady, M. E., Mara, C. A., Geiger-Behm, K., Ragsdale, J., Davies, S. M., Schwartz, L. A., Phipps, S., & Pai, A. L. H. (2021). Psychometric evaluation of the brief RCOPE and relationships with psychological functioning among caregivers of children undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplant. Psychooncology, 30(9), 1457-1465. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5705

Moroń, M., Biolik-Moroń, M., & Matuszewski, K. (2022). Scrupulosity in the network of obsessive-compulsive symptoms, religious struggles, and self-compassion: A study in a non-clinical sample. Religions, 13(10), 879. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13100879

Nurasikin, M. S., Khatijah, L. A., Aini, A., Ramli, M., Aida, S. A., Zainal, N. Z., & Ng, C. G. (2012). Religiousness, religious coping methods and distress level among psychiatric patients in Malaysia. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 59(4), 332-338. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764012437127

Paika, V., Andreoulakis, E., Ntountoulaki, E., Papaioannou, D., Kotsis, K., Siafaka, V., Fountoulakis, K. N., Pargament, K. I., Carvalho, A. F., & Hyphantis, T. (2017). The Greek-Orthodox version of the Brief Religious Coping (B-RCOPE) instrument: Psychometric properties in three samples and associations with mental disorders, suicidality, illness perceptions, and quality of life. Ann Gen Psychiatry, 16, 13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12991-017-0136-4

Pargament, K., Feuille, M., & Burdzy, D. (2011). The Brief RCOPE: Current psychometric status of a short measure of religious coping. Religions, 2(1), 51-76.

Rosa-Alcázar, Á., García-Hernández, M. D., Parada-Navas, J. L., Olivares-Olivares, P. J., Martínez-Murillo, S., & Rosa-Alcázar, A. I. (2021). Coping strategies in obsessive-compulsive patients during Covid-19 lockdown. Int J Clin Health Psychol, 21(2), 100223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijchp.2021.100223

Rosellini, A. J., & Brown, T. A. (2010). The NEO Five-Factor Inventory: Latent structure and relationships with dimensions of anxiety and depressive disorders in a large clinical sample. Assessment, 18(1), 27-38. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191110382848

Rosmarin, D. H., Kumar, P., Kaufman, C. C., Drury, M., Harper, D., & Forester, B. P. (2024). Neurobiological correlates of religious coping among older adults with and without mood disorders: An exploratory study. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging, 341, 111812. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pscychresns.2024.111812

Sauer-Zavala, S., & Barlow, D. H. (2021). Neuroticism: A new framework for emotional disorders and their treatment. The Guilford Press.

Schuster, M. A., Stein, B. D., Jaycox, L. H., Collins, R. L., Marshall, G. N., Elliott, M. N., et al. (2001). A national survey of stress reactions after the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. New England Journal of Medicine, 345, 1507–1512.

Tarakeshwar, N., Pearce, M. J., & Sikkema, K. J. (2005). Development and implementation of a spiritual coping group intervention for adults living with HIV/AIDS: A pilot study. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 8(3). https://doi.org/10.1080/13694670500138908

Tavernier, R., Fernandez, L., Peters, R. K., Adrien, T. V., Conte, L., & Sinfield, E. (2019). Sleep problems and religious coping as possible mediators of the association between tropical storm exposure and psychological functioning among emerging adults in Dominica. Traumatology, 25(2), 82-95. https://doi.org/10.1037/trm0000187

Tellegen, A. (1985). Structures of mood and personality and their relevance to assessing anxiety, with an emphasis on self-report. Anxiety and the anxiety disorders. (pp. 681-706). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

VanderWeele, T. J., Yu, J., Cozier, Y. C., Wise, L., Argentieri, M. A., Rosenberg, L., Palmer, J. R., & Shields, A. E. (2017). Attendance at religious services, prayer, religious coping, and religious/spiritual identity as predictors of all-cause mortality in the black women’s health study. American journal of epidemiology, 185(7), 515-522. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kww179

Watson, D., & Clark, L. A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of personality and social psychology, 54(6), 1063-1070. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063

Wilt, J. A., Stauner, N., Harriott, V. A., Exline, J. J., & Pargament, K. I. (2019). Partnering with God: Religious coping and perceptions of divine intervention predict spiritual transformation in response to religious−spiritual struggle. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 11(3), 278-290. https://doi.org/10.1037/rel0000221

Zhang, L., & Takahashi, Y. (2024). Relationships between obsessive-compulsive disorder and the big five personality traits: A meta-analysis. J Psychiatry Res, 177, 11-23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2024.06.033

Appendix A

Disclosure: I am asking you to complete this survey as part of the requirements for my statistics project in a graduate-level psychology course. Your answers will remain completely anonymous. No personal information about you will be linked to this survey. Please do not put your name or any other identifying information on the survey. The results of this survey will be used only for educational purposes and will not be published or released to the public. You must be 18 years old or older to complete this survey.

- What is your age? __________

Directions: Think about how you try to understand and deal with major problems in your life. To what extent is each involved in the way you cope?

- Wondered whether God had abandoned me.

| Not at all

1 |

Somewhat

2 |

Considerably

3 |

A great deal

4 |

- Felt punished by God for my lack of motivation.

| Not at all

1 |

Somewhat

2 |

Considerably

3 |

A great deal

4 |

- Wondered what I did for God to punish me.

| Not at all

1 |

Somewhat

2 |

Considerably

3 |

A great deal

4 |

- Questioned God’s love for me.

| Not at all

1 |

Somewhat

2 |

Considerably

3 |

A great deal

4 |

- Wondered whether my church had abandoned me.

| Not at all

1 |

Somewhat

2 |

Considerably

3 |

A great deal

4 |

- Decided the devil made this happen.

| Not at all

1 |

Somewhat

2 |

Considerably

3 |

A great deal

4 |

- Questioned the power of God.

| Not at all

1 |

Somewhat

2 |

Considerably

3 |

A great deal

4 |

Directions: This scale consists of a number of words that describe different feelings and emotions. Read each item and then select the appropriate answer. Indicate to what extent you have felt this way during the past few weeks.

| Very slightly or not at all

1 |

A Little 2

|

Moderately

3 |

Quite a bit 4

|

Extremely

5 |

| __ irritable

__ alert __ ashamed __ inspired __ nervous __ determined __ attentive __ jittery __ active __ afraid

|